The Infinite Loop Method by Chris Sheridan

The Two Person Continuous Loop System, aka The Infinite Loop Method

For a long time now, I’ve wanted to (and attempted to) climb The Diamond on Longs Peak in the winter. Each attempted has ended for one reason or another: pinned down by a blizzard at the base of the North Chimney, a partner with altitude sickness after a bivy on Broadway, ext.

The most memorable precursor to retreat was looking down at my partner after leading the first 100ft of D7, he was shivering more and more the longer he sat there. It was still early in the morning; the sun was still on the face, but it wouldn’t be there for long. In order to move fast, we planned on the conventional strategy of leading long, rope-stretcher pitches and leading in blocks. But obviously, there was no way he could stay warm while sitting stationary through a long belay. On the other hand, if we did shorter pitches, we most likely wouldn’t make it to the top before the end of the day.

A year or so later, I ran into Joe who had also attempted The Diamond in winter. He mentioned trying to use short fixing tactics as a means of both moving a bit faster, and staying warm. The idea was that if the leader placed an anchor before the end of the pitch, and continued upward while self-belaying, the second could start cleaning the pitch sooner, and both people would keep warm.

Traditional Short Fixing

Short fixing strategies have been developed and employed primarily in Yosemite, where bolted belays are often established about 150ft apart. The general idea is that the leader arrives at a bolted belay and sets up an anchor, but he still has maybe 40ft of rope left. Instead of sitting around waiting for his partner to arrive at the anchor, he starts rope soloing the next pitch. Because cleaning a pitch usually takes far less time, the second typically shows up at the belay when the leader is about twenty feet up the next pitch. It then takes the team a few minutes to pass gear up to the leader. The leader may still not be at the end of the rope, so the slack in the rope as to be carefully transferred back to the second in order to put the leader back on a traditional belay. This all takes a fair amount of time, but hey, the leader is twenty feet up the next pitch.

When you take these basic strategies and apply them to aid climbing on a cold alpine wall, there’s still a lot to be desired. Leading 150ft before setting an anchor still leaves the belayer courting hypothermia. The twenty or so feet the leader advances is nearly negated by the time it takes to shuffle the rope and put him back on belay. Finally, the rack needed to lead 170ft is a pain in ass to carry all the way in to mountains.

The Infinite Loop Method

The new Infinite Loop method builds upon the continuous loop method for aid soloing as discussed on www.rockclimbing.com. Keep in mind that this is a very complex system and as usual, messing it will likely result in a very bad day. Each person involved should have ample experience with rope soloing, and the climb should offer some good, solid pro at least every 20ft or so. This is not a good way to belay A4 terrain.

At the base of the route, the team flakes out the rope with the middle of the rope at the bottom of the pile, and ties the ends of the rope together with an in-line figure-8 knot. The leader then attaches a solo belay device to the rope, right next to the knot. A Grigri works best, but which ever device is use, the leader should load the rope into the device with the knot on the “climber” side of the device and clip it to his belay loop. The side of the rope coming out of the “climber” side of the Grigri will hereafter be referred to as the lead side of the rope, while the side of the rope coming out of the “hand” side of the Grigri will be referred to as the “tag” side of the rope. To double check the setup, the leader can give the knot a sharp tug. If the Grigri doesn’t lock up, something’s wrong.

Next the second attaches his belay device to the lead side of the rope, a few feet away from the leader, then the leader can start up the first pitch. At first it takes a bit of care to make sure that the leader clips the lead side, and not the tag side, of the rope through the protection as he goes. If the leader falls, the leaders and seconds belay devices will lock up, and the fall will be caught as normal.When the leader is about half a rope length up the first pitch, he places a reasonable belay anchor and fixes the lead side of the rope to the anchor. A butterfly knot, just beyond the in-line figure-8 works will for this purpose. Unlike a typical belay anchor, this anchor is never the only anchor holding the climbing team to the rock; two good equalized pieces may be all that are needed. We’ll call it a mini-belay.

When the first anchor is set, the second starts ascending the lead side of the rope, and the leader keeps on climbing. Starting at this point, the leader begins belaying himself with his Grigri, passing rope from the tag side of the rope, through the Grigri, to the lead side of the rope. Meanwhile, the second is ascending the rope cleaning pieces as he goes. Cleaning the lower pieces makes more rope available on the tag side of the rope, so the leader never runs out of rope. Once the team is done with this initial setup phase, they can keep on going indefinitely, so long as they stick to the following guidelines.

- The Leader should place a new mini-belay and fix the rope every 80ft or so.

- The second should never clean one mini-belay until the next has been placed.

- The second should never get too close to the leader. Keep at least one mini-belay, and three bomber pieces between the leader and the second. This is key to making the mini-belay concept work. Otherwise, closer is better, as it leaves more gear at the disposal of the leader, helping him go faster.

- The leader will naturally set the pace of the team, so the second should take the time to sort gear well, and send it up to the leader when needed using the tag side of the rope.

- The second should also carry most of the group gear that isn’t being used.

Every rope length, the leader will need to pass the knot in the lead rope. The leader should make sure to have a back up during this transition. One way is for the leader to place a mini-belay when he reaches the knot. That way he can clip into the mini-belay and one other piece while re-configuring his belay device. Clipping directly into the rope with a figure-8 on a bite would also make a good back up.

Once the leader gets going, it will be a long time before he and the second are in the same place at the same time. He should stuff his pockets with plenty of GU and bars, bring a water bottle, and take the time to eat and drink regularly.

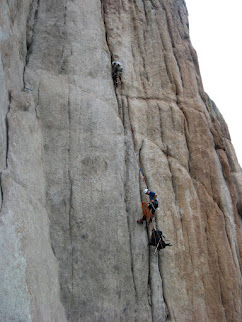

I gave this system a try with my friend Andy on a winter day at Lumpy Ridge. We climbed a link up of Howling at the Wind, Cheap Date, and Outlander. Right away we noticed numerous significant advantages. For starters, you don’t need nearly as much gear as conventional aid climbing. The leader is never more then half a rope length above the second, so there aren’t nearly as many pieces in the rock at any one moment.

You don’t need a second rope or tag line because the tag side of the rope can be used to pass gear up to the leader. If you need another rope for the decent, you can keep it in the second’s pack and save lots of time in rope management. The second can carry a reasonably heavy pack without slowing the team down. The lead rope never has to be stacked or flaked or shuffled back and forth, and finding two good pieces for a mini-belay is much faster and less gear intensive then setting a full, three point, equalized anchor.

Though developed with alpine aid in mind, the Infinite Loop method works just as well on a warm sunny big wall. Hauling a haul bag is out of the question, so think in-a-day routes or the summit push.We climbed our practice route in one long block, and both stayed warm because we each stayed moving the entire time. Overall, we shaved over two hours off of our time from the same route using traditional short fixing tactics.

Bio: Chris Sheridan works as a Mechanical Engineer in Boulder, CO during the week, and attempts to climb in Rocky Mountain National Park during the weekends.